Another lovely review of Manan, by LiveMint

Here's the link to the review: http://www.livemint.com/Leisure/5tvlimit4QdpplDtpGnNdJ/Young-Lit--Manan.html

Once again, pasted below in full without permission :)

We have been there, done that. This, in large part, is the draw of Mohit Parikh’s debut novel Manan, which gives a realistic account of a few significant days in the life of a teenage boy, growing up in an Indian city in the 1990s.

A late bloomer, the eponymous hero is sent into a tizzy by a wonderful (for him), though ordinary (otherwise), discovery: his first pubic hair. To Manan, it appears to be an answer to all his prayers. It is a remedy to the grave injustice that he sticks out among his peers, not having shot up—in spite of being the “eighth-oldest” person in his class and aged fifteen-and-a-three-quarter years. That he does not know as much about sex as his friends do is more humiliation than he can bear. The hair encourages him to address this lack of knowledge immediately.

But sex isn’t the only thing on his mind, where Super Mario video games, a constant war on his family’s superstitious beliefs, and real-life applications of scientific truths also jostle for space. Parikh makes it easy to slip under Manan’s skin, painting his inner world through daydreams. Everyday triggers, like the school bell announcing the end of lunch break, spark elaborate feats of visualization in him. He doesn’t just respond by rushing back to class, but takes a moment to consider how the sound travels in waves, ricocheting off the walls and ceilings, seeping through the floors, before setting his own eardrums vibrating.

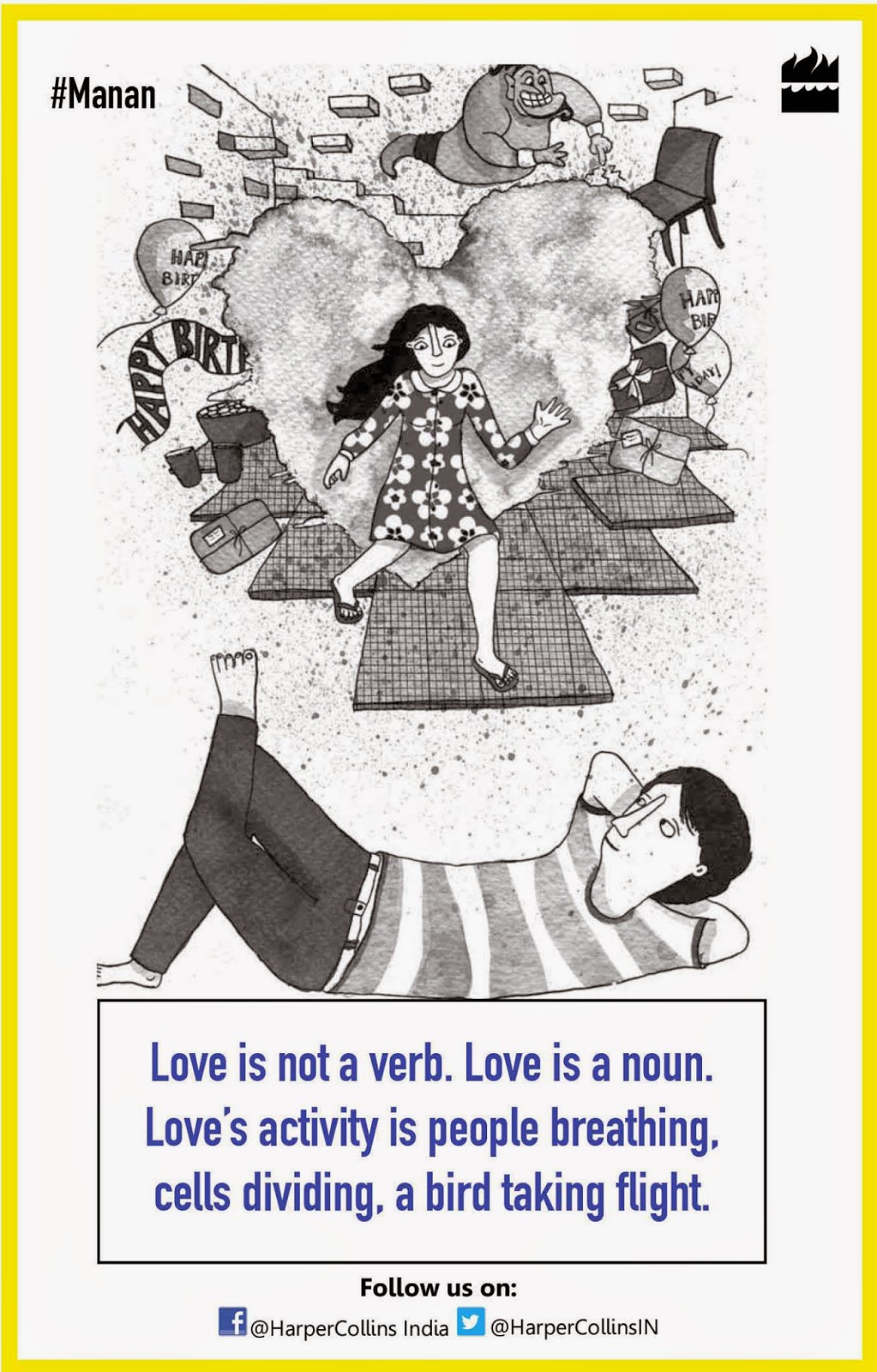

The illustrations by Urmila Shastry work well to supplement Parikh’s descriptions though, more often than not, readers won’t need these to imagine the scenes. One of the more interesting artworks, printed across two pages, shows a convergence of several things. At this moment in the story, Manan has been told off by his mother for eating mangoes on the veranda in case he catches the evil eye, when he “imagines an evil eye wandering in the crowd, a large single transparent human eye visible to no one but him. It makes searching sweeps, left to right, right to left, searching for those who eat indecorously or outside. The eye stops in front of him: locks him as a target and focuses all its laser power on his stomach to trouble his digestive system. He makes Mario jump on it and crush it out of life.” In the drawing, a giant human eye—the kind of diagram readers may remember making in biology class at school—is shown walking towards Manan in a parody of the superstitious evil eye, as Mario uses a wall for leverage, presumably to jump on the offending eye.

Parikh exercises restraint throughout. The language, while descriptive, is never excessive or showy. Fragments such as “Incisors, molars, swallow” pithily describe Manan eating a snack. Students play “answer sheets aeroplane” after class. Not only do you get what Parikh means, better still you see it in the mind’s eye. Most young-adult novels try to create new worlds. Manan tries to recreate a world most of us have lived in. Parikh achieves this by peppering the narrative with detail. Some of the incidents, such as Manan skipping a day of school or spotting the girl he likes at the market, are universal enough to speak to any generation.

Other episodes, such as the time he reads R.K. Narayan’s The Missing Mail at school, or speaks of the Internet cafés just beginning to open in Indian cities, or describes the canteens, corridors, classrooms and clubs, may resonate with those who grew up in the last years of the 20th century. Such readers may be left with the feeling of having known someone like Manan in their teenage years. Or having been such a teen themselves.

Comments

Post a Comment